Chapter 17 - The Dutch Fork Settlement and the Capture of Jacob Miller: 400 Years in America

The American Revolution on the Western Frontier Part II: The Dutch Fork Settlement

The Ohio Frontier during the Revolution

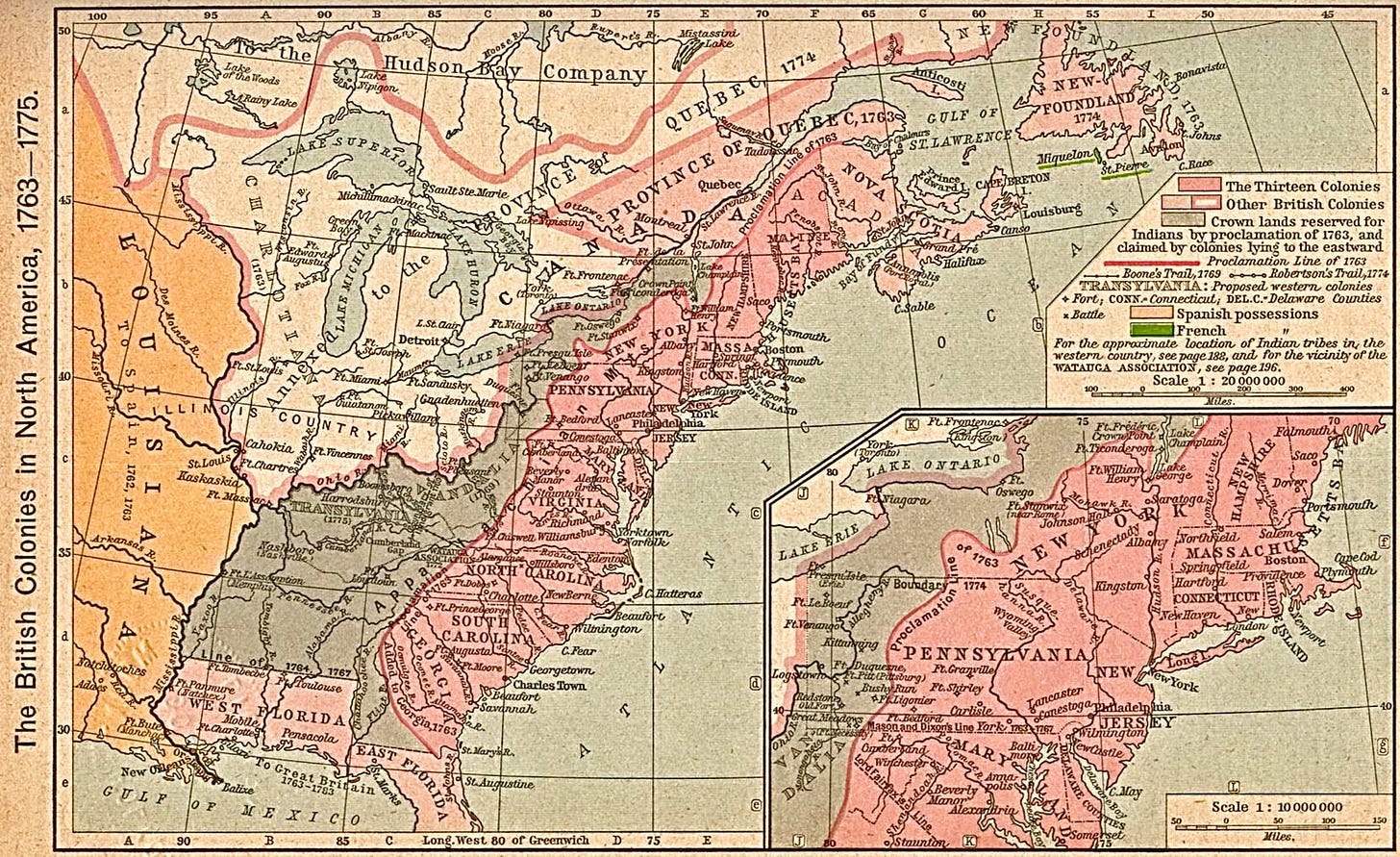

At the time of the Revolution, present day Ohio, like most of the land west of the Appalachian Mountains, was reserved for Native Americans. After Britain defeated France in the French and Indian War, the Colonists hoped to continue moving west across the Appalachians. But the Royal Proclamation of 1763 placed a boundary on the colonies, right down the spine of the Appalachian range. Everything west of the Proclamation Line was to remain Indian territory. All private individuals were prohibited from buying these lands. (Calloway, 2018).

Above: Map of the British colonies in North America, 1763 to 1775, first published in Shepherd, William Robert (1911) "The British Colonies in North America, 1763–1765" in Historical Atlas, New York, United States: Henry Holt and Company, pp. p. 194. Public Domain.

One often-overlooked complaint of the American Colonists that led them to declare independence from the British was the Quebec Act of 1774. In this act the British extended the province of Quebec to include the entire area west of the Applachians, including land that is now southern Ontario, Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, and parts of Minnesota.

The Quebec Act made French the language for civil law matters, guaranteed the rights of Catholics, including the right of the Catholic church to impose tithes, and voided any land claims of colonists to the Ohio Country, effectively stopping further western expansion. (Calloway, 2018)

The Act was passed in the same Parliamentary session as the other Acts designed to punish the colonists for the Boston Tea Party. It was also seen by the colonists as the establishment of Catholicism as a state religion, and was labeled as one of the “Intolerable Acts.”

Our ancestors were anxious to get to the rich western lands. The Quebec Act was an attempt to bottle up the colonists east of the Appalachians and cement the loyalty of French Canadians to their new British overlords. It failed to do either.

The Dutch Fork Settlement

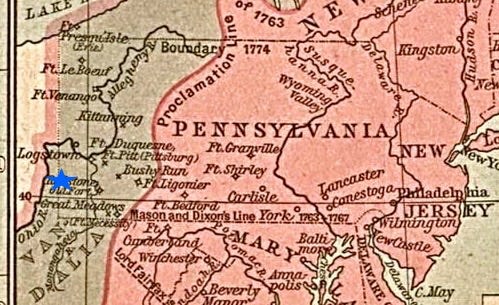

West of the Appalachians, and east of the Ohio River, the Dutch Fork of Buffalo Creek area is beautiful even today, with a large man-made lake known as Dutch Fork Lake, just north of Interstate 70 west of the Claysville, Pennsylvania exit. It is 44 miles southwest of Pittsburgh, then known as “Ft. Pitt.”

At the time of the Revolution the creek known as Dutch Fork flowed into Buffalo Creek then to the Ohio River, about 13 miles northwest. George Washington had surveyed this area after the French and Indian War, only to have his patents disallowed by the British. Both the Pennsylvania and Virginia Colonies claimed the Dutch Fork region.

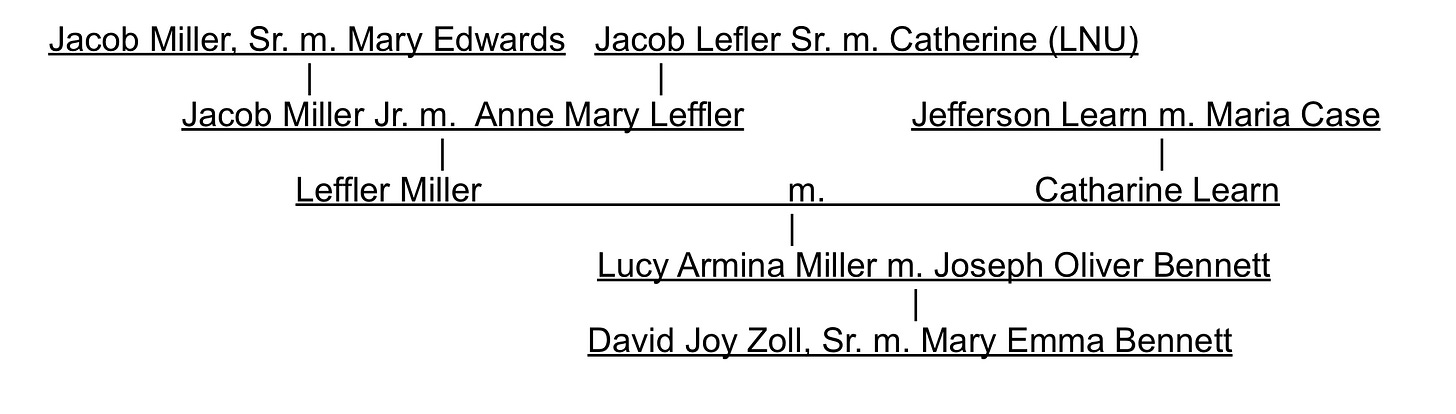

There were five families who, in the same year that the Quebec Act was passed, 1774, moved over the mountains and settled in the beautiful Dutch Fork region. Two of these pioneer families, the Lefflers and the Millers, are our ancestors. Leffler Miller, grandson of both Jacob Miller and Jacob Leffler, for whom he was named, would marry Catharine Learn, granddaughter of John Learn, the sole survivor of the Learn Massacre. They are buried in Putnam County, Ohio.

Jacob Lefler was born in Hagerstown, Maryland in 1745. His oldest child, our ancestor Anne Mary Leffler, was also born in Hagerstown. In 1774 the family moved west of the Appalachians to the Dutch Fork area. Jacob Lefler claimed a 400 acre tract on Dutch Fork which he called “Sylvia’s Plain.” This was true frontier. They had no one to rely upon but themselves and their neighbors. The Leffler’s and most of the people who settled this area were Swiss, but we have no certain record of their immigration.

Another ancestor family who moved to Dutch Fork at this time was Jacob Miller and his wife Mary, along with their children. They too were of Swiss origin. One of their sons, John Jacob Miller, would soon marry Anna Mary Leffler, daughter of Jacob and Mary Leffler. This John Jacob Miller, son of Jacob Miller, will be referred to here as Jacob Miller, Jr. We believe the elder Jacob Miller, Sr. immigrated from Switzerland about 1753. Jacob Miller Sr.’s 400 acre plot was called “Wild Cat’s Forest.”

The blue star marks the approximate location of the Dutch Fork Settlement. You can see that the settlement was located in the lands forbidden to white settlers by the British.

After the 1776 Declaration of Independence the Dutch Fork area was designated as Ohio County, Virginia. The men of Dutch Fork organized into a militia in 1777 as part of the Ohio County, Virginia militia. All males took the oath of loyalty, including our ancestors Jacob Miller, Sr., his son Jacob Miller, Jr. and Jacob Leffler, Sr., father of Anna. Jacob Leffler, Sr. was elected Captain.

In 1780 Jacob Miller Sr. received a “Virginia Certificate of Survey” for his 400 acres known as “Wild Cat’s Forest,” and on the same date Jacob Leffler received a “Virginia Certificate of Survey” for his 400 acres known as “Sylvia’s Plain.” These certificates recognized their prior settlement claims from 1774.

In 1780 the settlers built blockhouses, which were small log forts, where they could go in case of an attack by the Native Americans.

In April, 1781, the men of Dutch Fork were still serving in the Virginia Militia. They were engaged in an expedition for a period of 19 days under General Brodhead against the Delaware Indians at Coshocton, Ohio. Soon thereafter the Dutch Fork area was transferred from the state of Virginia to the state of Pennsylvania. The militia was reorganized as the Washington County Pennsylvania Militia.

The following story is based on an article that appeared in The Intellligencer, Wheeling West Virginia 1864, reprinted in the September 18, 1882 edition of The Intelligencer.

The Capture of Jacob Miller, Jr., September 1781

Jacob Miller, Sr. had built a blockhouse atop a bold bluff on the right bank of the Dutch Fork of Buffalo Creek, about 3 miles northeast of the present day town of West Alexander, Pennsylvania. In the summer months when the weather turned nice, families would move to the blockhouses for protection from Indians, who would take advantage of the fair weather to cross the Ohio River and attack settlements south and east of the big river.

Early one fine September morning in 1781, our ancestor, Jacob Miller, Jr., age 19, left the blockhouse his father had built along Buffalo Creek. With him were Frank Hupp and Jacob Fisher. Their goals were to look for stray horses and scout for Native Americans, who were a constant threat during the summer months. Each of the three men carried a rifle, powder, and ball shot. They headed west northwest into the forest towards the Ohio. Only Jacob Miller would return.

After an unsuccessful day of searching and scouting, they found themselves at nightfall at the cabin of Jonathan Link, on Middle Wheeling Creek. Here they were welcomed and spent the night. They slept restlessly that evening, as their dogs kept barking fiercely, presumably because of nearby wolves. But a band of Natives had crossed the Ohio and were hidden in careful ambush near the door and pathway to the Link cabin in which they had taken refuge.

As Hupp and Fisher left the Link cabin and headed to the nearby spring to refresh themselves, a volley of shots rang out. Fisher fell dead. Hupp, mortally wounded, rushed back into the cabin, followed by the attackers. Miller and Link had no time to charge and fire their weapons, instead complying with the demands of the Indians to surrender. Hupp was scalped on the spot.

The Indians, with our ancestor young Jacob Miller a prisoner in tow, then attacked the Presley Peak cabin, several miles to the northeast, capturing three more men: Peak, William Hawkins and a man named Burnett. Binding them as well, the raiders moved further east to the cabin of William Hawkins, who had already been captured. Although his family had escaped, left behind in the cabin was his daughter, Elizabeth Hawkins, who was ill. She too was captured and the war party moved further on to the Gaither cabin. However the Gaither’s had heard the shooting and rushed away into the forest, leaving their cooked dinner behind. The warriors enjoyed the meal and celebrated their success.

A war council was held. The five male captives were bound and seated on a log. Behind each of them stood a powerful warrior with a tomahawk in hand. Suddenly three of the five captives were tomahawked and lay dying. Two of the warriors seemed to have doubts and did not swing their weapons, though they kept them raised. In this moment of suspense, Miller and Link kept their composure, sitting bravely erect. A mournful songbird called out just then, and the two executioners returned their tomahawks to their belts in the face of the courage shown by Miller and Link.

Miller and Link, along with Miss Hawkins, were quickly led north, to the banks of Big Wheeling Creek. A supper was cooked, the fire extinguished, and the male prisoners were tied with rawhide strips to their Indian captors, who laid down on either side of them to sleep.

Miller, knowing his life was at stake, chewed through the tough leather thongs that bound him so tightly, escaping while his captors slept. By dawn he had arrived safely back at the Miller Blockhouse. Here he broke down sobbing as he told the story, the deep purple welts on his arms stark evidence of his captivity. Recovering his composure, he lead a party of men back to the gruesome scenes where the victims were buried.

Jonathan Link was not as fortunate as Jacob Miller. Link was transported over the Ohio by his captors, then, according to tradition, brought back to his old neighborhood and used as target practice by his captors in sight of his cabin.

Miss Hawkins was eventually wed to a Shawnee chief. Years later she returned to see her old home, but found civilization too boring, and chose to return to the freedom of her life as a Native.

In his later years Miller could seldom be induced to recite the story. When he did, he could not do so without “tears streaming down his manly cheeks.”

Sources:

Lobdell, Jared. Indian Warfare in Western Pennsylvania and North West Virginia at the Time of the American Revolution, Appendix II, Dr. J. C. Hupp, “History of the Attack on Link’s Blockhouse”, Google Books, Heritage Books, 1992.

The Dutch Fork Settlement, by Raymond Martin Bell, unpublished, Washington, Pennsylvania, 1983, accessible on line and at the Genealogical Department of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Colin G. Calloway (2018), The Indian World of George Washington: The First President, the First Americans, and the Birth of the Nation, Oxford University Press.

Various Military pay records.

Note: An earlier version of this Chapter omitted the capture and escape of Jacob Miller.

Read Chapter 1: 400 Years in America.

Read Chapter 16, The Western Front during the Revolution: The Learn Massacre: 400 Years in America.

Enlightening. Thank you

Oh My God. There is so much in this. You must have had a fantastic time researching all this family history or maybe you inherited some research and verified and augmented it. That very uncharacteristic John Wayne film in which he never quite convinced us he's the Good Guy 'The Searchers' has that theme,kidnapped children who grew up to enjoy being Injuns. I've read that Wayne didn't want to do that movie but his friend John Ford made him because he could. It's more interesting than most Westerns. See,by today's standards WE,US BRITS were THE GOOD GUYS. We set a Boundary and told the Native People,no further,we recognise it's your land. Our King George III "Farmer George" didn't approve of the land take over but all through human history such arbitrary borders never work in reality. It's tricky for me here because from one point of view I have to ideologically condemn your ancestor but people have to do this,expand,explore,- go forth,risk,offend as human beings we can't just sit in a tidy box all our lives. Well,with all your amazing links to the earliest times in USA you ARE Mr America - Mr Zoll.🇺🇲 I hope this is the correct flag!