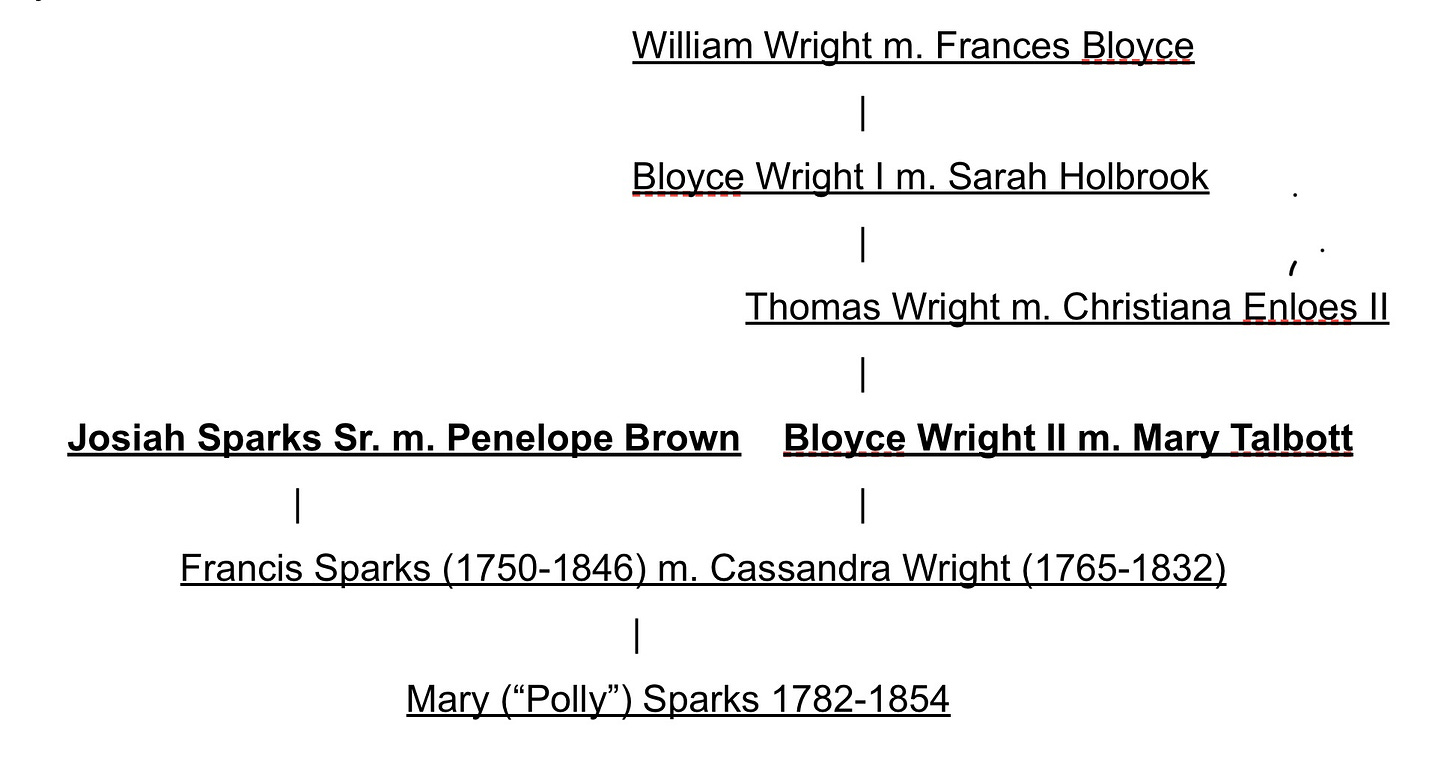

The Colony of Maryland was founded as a haven for Roman Catholics seeking to escape religious persecution in England. This chapter will focus on some of the ancestors of Mary “Polly” Sparks, born 1782 in My Lady’s Manor, Baltimore, Maryland. In doing so we will necessarily shine a light on the barbarous practice of slavery.

Polly Sparks married John Sharp in Maryland in 1810, then moved with him and their children to Fairfield County, Ohio. When John Sharp died, Polly married Elias Isaac Decker, with whom she had three children, including Elizabeth Decker. The family moved from Fairfield County to Hancock County in 1833 at the same time as the Zoll clan, and Elizabeth married William Harrison Zoll in Hancock County, Ohio in 1845.

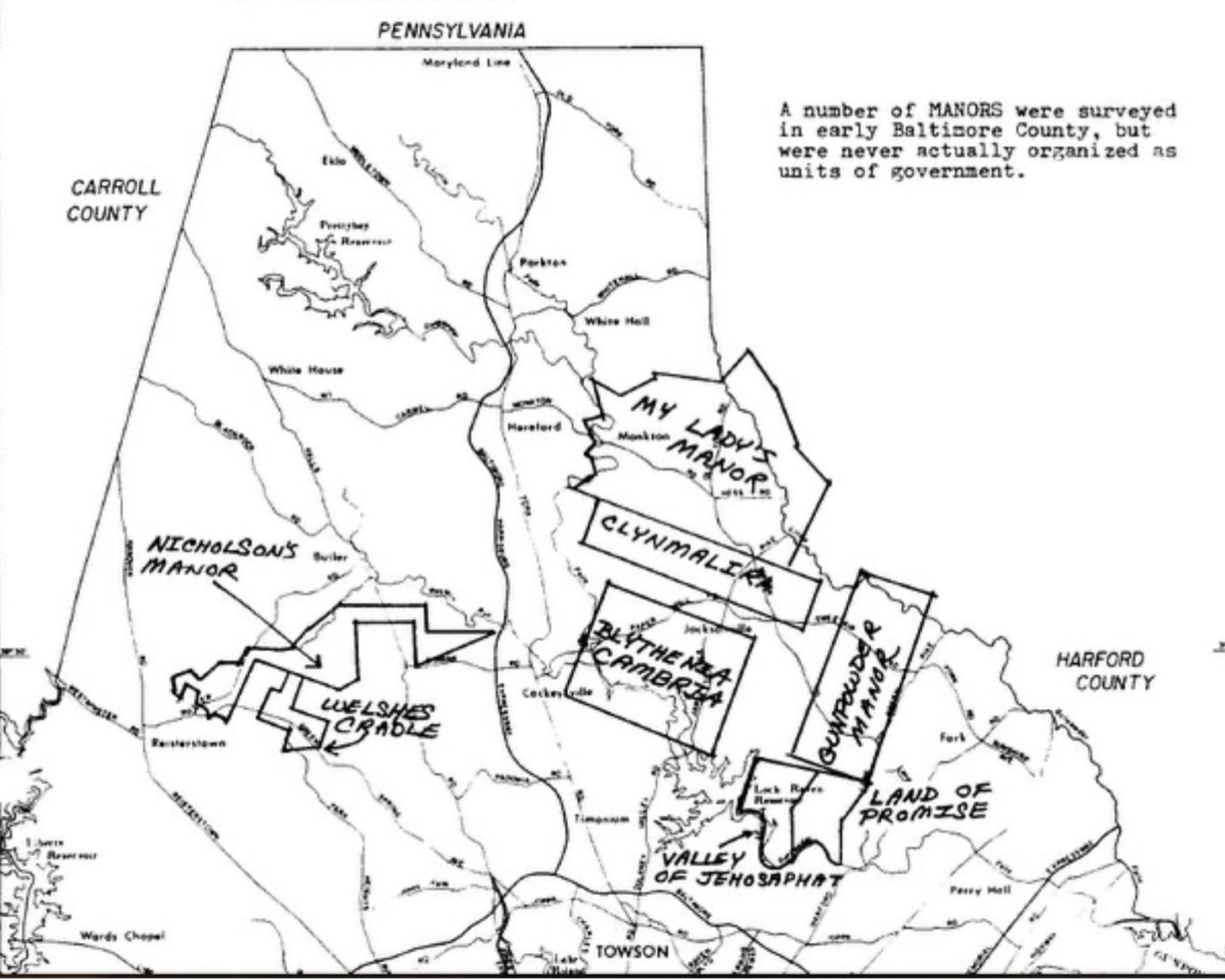

“My Lady’s Manor,” where Polly Sparks was born, was neither a house, nor a town. Rather it was a 10,000 acre (more than 15 square miles) tract of land north of Baltimore that was owned by the third Lord Baltimore, and given to his fourth wife in 1713 at the time of their marriage. It continued to be owned by British lords and ladies until the American Revolution, after which the land was auctioned off.

The British lords and ladies didn’t actually live on the land; rather they rented it out to tenants. The rent was paid in tobacco. When Polly and her then husband John Sharp left Maryland for Ohio about 1810, the hard work of tobacco farming was being done by slaves. That would continue until November 1, 1864.

Polly Sparks’ ancestors had been in Maryland since it was first founded. Let’s look at each of her four grandparents for a deeper understanding of this branch of our family tree.

Josiah Sparks and Penelope Brown

Polly’s paternal grandfather, Josiah Sparks, Sr. was born in 1727 in Anne Arundel County, no doubt on a tobacco plantation. His grandfather was most likely Richard Sparks (the great great grandfather of Polly) who was born in Farnham, Hampshire, England, near Portsmouth, in the year 1658.

Richard Sparks arrived on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in 1673 at the age of 15 as an indentured servant, and worked for his freedom for at least seven years in the tobacco fields. At that time young strong men were given free passage to Maryland in exchange for five to fifteen years of work raising tobacco. In later years this work would be done by slaves, but initially poor white English and Irish were enticed into contracts that required them to work long hours in difficult conditions. The person who paid for the “transport” of an indentured servant received 50 acres of land for each person “transported.”

By the time Richard Sparks’ grandson Josiah Sparks was born, the Sparks family were well-off planters. Josiah Sparks married Penelope Brown on July 15, 1749. He was 22 and Penelope was only 17. They were married in the Anglican Church of St. Anne’s parish in Annapolis, Maryland.

Penelope’s grandfather, William Browne, also arrived as an indentured servant with the first ship of Maryland settlers in 1634. The records from the early years of the Maryland Colony are few and far between. The first successful settlement was in 1634 when two ships, the Ark and the Dove left England, supported by Lord Baltimore, who had obtained a charter for the colony from King Charles. The ships landed at St. Clement’s Island on March 25, 1634, and soon thereafter made friends with Yaocomico Indians, from whom they purchased land and established the town of St. Mary’s.

Of the approximately 300 passengers on the two ships, 18 were “Gentlemen” and the rest were indentured servants, required to work for 5 years in exchange for their passage, after which they were freemen. The person responsible for transporting each passenger was entitled to receive 50 acres of land for each person they transported. The passenger lists from those ships has never been found; however the land records state that William Browne was transported in the ship Dove as an indentured servant. Indentured servants provided most of the labor on the plantations at first.

Josiah Sparks died at the age of 38. Penelope remarried and moved just north across the state line to York, Pennsylvania. However we have the will of Josiah Sparks, Jr., (oldest son of Josiah and Penelope, the brother of Francis, and the grandson of Richard Sparks, not directly in our line) that clearly show they were slave holders. Josiah Sparks Jr. died in 1846 at the age of 90 and left the following legacy in his will:

“My coulored woman Marenda. I leave to go free when I am no more. My black man Joshua, I leave to go free when I am no more. I give and bequeath unto my daughter Ruthy Pierce one black girl till she is 25 years of age and then to go free named Nelly to serve her till she is 25 years old and then to go free. I give and bequeath to Ellen Sparks wife of Frances Sparks one black girl named Sarah Ann to serve her till she is 25 years old and then to go free. I give and bequeath unto Aaron my son one black boy named James and one black girl named Elisabeth, to serve him till they are 25 years old and then they are to go free. I give and bequeath unto my daughter Sarah Maze three black boys by name Nelson, John and Thomas to serve her till she is 25 years old and then they are to go free, the black boy Nelson to be taken by my son Frances when he arrives at 18 years of age and he is to pay the said Sarah Maze twenty dollars per year till he is 25 years old.” (Josiah Sparks’s Will 92).

Receipt for transporting Thomas Browne on the Ship Dove

:

Bloyce Wright II and Mary Talbot

Polly Sparks maternal grandmother was Mary Talbott. Mary was born in Hanford County, Maryland just east of My Lady’s Manor, most likely on a tobacco plantation inherited by her father William Talbott from his father, Edmund Talbott. William Talbott left a detailed will which describes that he owned at least 300 acres of plantation. The land was divided among his four sons, and his “moveable estate” was divided one third to his wife and the balance divided among his children, including Mary. He bequeathed his copper still to his wife.

Edmund Talbott, Mary’s grandfather and Polly’s great great grandfather, died in 1731. He too left a detailed will. Edmund had three sons and one daughter. Each child was given a fifty acre plantation. I quote here from the second “Item” of Edmund Talbott’s will:

Item. I give and bequeath unto my beloved Wife Mary my Negro Man and Woman during her Natural life unless she should Marry another husband and then my Will is that the Said Two Negroes may be sold and the Money equally divided amongst my four Children above Named My Wife having her Thirds and first choice.

Mary Talbot, granddaughter of Edmund, married Bloyce Wright II at St. John’s “Gunpowder” Parish, Maryland when she was 20 years old. The Episcopal parish extended from the Gunpowder River to the head of St. John’s River “as far as the County goes or extends.” Bloyce Wright was born in White Hall, Maryland, on the Gunpowder River, probably on the same plantation where he died. He was named after his grandfather, Bloyse Wright I (1681-1737). “Bloyse” was his mother Frances’ maiden name (1648-1761). Early land records from Somerset, now Wicomico County, Maryland, state that a survey was done in 1666 for Thomas Bloyce for 150 acres of land possessed by Bloyce Wright known as “Bloyce’s Hope.”

Frances Bloyse and William Wright were married December 7, 1669. William and Frances had at least six children. I will quote now from The Wright Ancestry of Caroline, Dorchester, Somerset and Wicomico Counties, Maryland, by Charles Willis Wright, 1907.

It does not matter as much whence we came,

As it does where we are going.

C. W. W.

…

Possibly nothing in this book will attract more attention, or cause more surprise, than the next two paragraphs, which give an account of what appears to have been marks upon slaves and by which they were identified. Many of the present generation and age, no doubt, are loath to believe that such barbarous method was resorted to; nevertheless it appears to have been legal and met with official approval, as it is of record, as follows:

Alos Wright, the daughter of William Wright, viz: the left ear creosote, with four finger & the third taken away entirely, second day June 1686.

Judith Wright her mark the right ear cropt with four finger & third taken away entirely. Second day of June 1686.

Blois Wright had a mark recorded in 1686, and others had registered marks also.

The Wright Ancestry, op. cit., pp 61-62, 1907

These three Wrights, Alos, Judith, and Blois, were all children of William Wright and Frances Bloyse. At the time these marks were recorded, each of these children was about five years old. They were given these slaves as young children. They grew up with the institution of slavery as an important part of their life. These were “religious” people.

Tobacco was used for money, and was grown by slaves. At first indentured servants did the work but eventually African slaves became the dominant workforce. In 1664 under the governorship of Charles Calvert, 3rd Baron Baltimore, the Assembly ruled that all enslaved people should be held in slavery for their life, and any children born “of any negro or other slave shall be slaves as their fathers were for the term of their lives.” This law was to prevent people from freeing their slaves.

Bloyse Wright bought 214 acres of land, called Richardsons Reserves, at the head of the Gunpowder and Middle Rivers. Bloyse paid for the land with 4,000 pounds of tobacco.

Bloyse Wright married Sarah Holbrook. Their son Thomas married Christiana (II) Enloes. Christiana (II) was named after her grandmother, Christiana (I), who was born in Baltimore in 1647. At the age of 21 Christiana (I) married Hendrick Enloes.

Hendrick Enloes (was born in Reusel-de Mierden, Nordic-Brabant, Netherlands in 1632 and came to Maryland sometime before 1673. In 1673 he acquired 100 acres in Dutch Neck, the 100 acre farm of Swallow Fork, and several other farms. But the Enloes were not our earliest Dutch ancestors in North America, as we will see in the next chapter.

When Polly Sparks left Maryland for the Ohio frontier sometime after the Revolution, she left slavery behind. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 made slavery illegal in the area that would become the states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin and parts of Minnesota.

https://csac.history.wisc.edu/2020/12/11/the-northwest-ordinance-13-july-1787/ Used with permission of the Center for the Study of the American Constitution, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Polly Sparks Decker died in Ohio in 1854. She would have been at the Ohio wedding of her daughter Elizabeth Decker to William Harrison Zoll in 1845. But she died before seeing her son in law William enlist in the Union Army to fight for the cause of freedom and the abolition of the institution of slavery. He was wounded at the Battle of Shiloh, as we will see.

Footnotes for Chapter 6

The original St. Anne’s Anglican Church in Annapolis was finished by 1704. The church bell was donated by the British Queen Anne. She detested Roman Catholics, and this may have partially motivated her to donate a bell to an Anglican Church in a Roman Catholic colony. Under Queen Anne’s rule, an agreement with Spain granted Britain a monopoly on the slave trade with Spanish colonies. Under the Treaty of Utrecht, 1713, the British South Sea Company was entitled to send 4,800 slaves to Spanish America every year for thirty years. Queen Anne held 22.5% of the stock of the South Sea Company.

The Slaves of My Lady’s Manor: The Sparks Family. https://rampantfoxes.wordpress.com/2014/08/20/the-slaves-of-my-ladys-manor-their-families-and-masters/ accessed June 28, 2023.

The Wright Ancestry of Caroline, Dorchester, Somerset and Wicomico Counties, Maryland, by Charles Willis Wright, 1907, Baltimore City Print. and Binding Co., 1907, accessed June 26, 2023, public domain, Google Book Search.

Chapter 7: New Amsterdam - The Dutch

Originally the Pilgrims had intended to settle near present day New York City. But the Dutch captain of the Mayflower made landfall at Cape Cod. Because it was so late in the year, their supplies were dwindling, and the weather was deteriorating, the Pilgrims decided to make do where they were and chose Plymouth as their site.

Chapter 1 Four Hundred Years in America

“Remember, remember always, that all of us, and you and I especially, are descended from immigrants and revolutionists." ― Franklin D. Roosevelt Copyright David W. Zoll 2024. All rights reserved. Cover Art by Hayley Joy BeckerThanks for reading David’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Partus sequitur ventrem ( that which is born follows the womb) was a change in the Virginia law in 1662 that said a child’s social status, free or slave, was to be determined by the mother. This legal change allowed a slave holder to increase his wealth by fathering children from slave women. After slave trading from Africa was illegal, Virginia became a slave exporter to cotton plantations in the deep south. In Annette Gordan-Reed’s book “Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings” the reader is brought face to face with a Hemings slave house servant who was not able to attend the funeral of her biological half sister (same father). In my opinion, the social damage of slavery goes much deeper than chattel property and the long lasting social destruction done continues today because we as a country have not publicly admitted the damage caused by slavery nor have we asked for forgiveness and offered reparations.

I lived in Maryland for 15 years. I loved the state from the mountains of western Maryland to the Eastern Shore. The history so interesting, but so sad, barbaric, and inhumane at the same time. I remember visiting St. Anne's Church in Annapolis. Beautiful, and seeing the Calverts and others buried in the church cemetery.