I mentioned this week that I worked for my Uncle John for two summers in a Sandusky, Ohio factory where he was the plant manager. In honor of the 4th of July, and in memory of the Greatest Generation, here is an excerpt from my book, “400 years in America.”

Above: John C. Good, his mother Ida Belle, and father John Wesley, review John C.’s Flight School Diploma and certificates before he leaves for combat in Europe. This photo, from a newspaper account in the local paper, hung in my Uncle Dr. Lowell Good’s office.

John Wesley Good and his wife, Ida Belle Knepper Good, had a family farm five miles west of Tiffin, Ohio. Seven children survived to adulthood, including my Mother. Her brother John, shown above with my maternal grandparents, was the oldest.

The United States was not prepared for war. The Navy and Air Force were small and outdated. For Germany to be defeated the United States would have to control both the sea and the airspace over Germany.

John Cyrus Good was drafted into the United States Army Air Corps on January 3, 1942, less than a month after Pearl Harbor. After basic training, Private John C. Good was sent to Sheppard Field, Texas, to Airplane Mechanics School, graduating August 8, 1942.

He completed ground school and flight school at newly built Grider Field, Pine Bluff, Arkansas, where he learned to fly. From Pine Bluff he was sent to Childress Army Airfield, Childress, Texas, for an 18 week long Bombardier Training School. He graduated October 7, 1943, trained in dead-reckoning navigation and precision bombing using the M Series Norden, S-1 Sperry, and D-8 bomb sights. John received his commission as a Second Lieutenant and granted ten days leave before reporting for duty at Salt Lake City, Utah. The picture above was taken during that ten days’ leave.

Shortly after arriving at Salt Lake City, John was assigned to B-24 Crew #553, attached to the 331st Bomber Group, and sent to Casper, Wyoming for Combat Training School, which lasted 4 months.

On April 2, 1944, Crew #553 took off from West Palm Beach, Florida in their new B-24J Liberator, serial number 42-94940. It was a Model J, built by the Ford Motor Company at Willow Run, Michigan, one of 8,685 B-24s that Ford would build at Willow Run.

They flew the B-24 on the Southern Route, departing from Florida to Panama, then along the Atlantic Coast down to Brazil, crossing the Atlantic into Africa, then north up the west coast of Africa, eventually arriving in England.

Hitler claimed it would take ten years for the United States to catch up with the German war machine. But within 2 1/2 years of Pearl Harbor, thousands of planes, tanks and landing equipment were shipped to England.

When John Cyrus Good and Crew #553 arrived in England they were assigned to the 8th Air Force, 2 BD Command, 2 CB Wing, 453rd Group, Squad 733, stationed at Old Buckenham Field, near Norwich, England, home of the 453rd Bomber Group. The 8th Air Force Group had 48 Bomber Groups.

Above: Patch of the 453rd Bomber Group. The 453rd flew its first mission on February 5th, 1944, and its last on April 12, 1945. A total of 259 missions were flown by the heavy B-24 Liberators, dropping 15,804 tons of bombs in 6,655 sorties.

During the first months of combat flights over Europe the average crew lasted just eight to twelve missions before being shot down or disabled. Therefore the US Army Air Force decided that 25 missions while serving in a heavy bomber of the 8th Army Air Force would constitute a ”completed tour of duty” because of the “physical and mental strain on the crew.”

John’s first mission was May 22, 1944 over Siracourt - St. Pol France. They dropped 6 one thousand pound bombs on a V-weapon site. The V-1 flying bomb was a Nazi unpiloted aircraft, like a cruise missile, made to terrorize London. The V-1 was first deployed on June 13, 1944 as “vengeance” for the D-Day landings. On some days more than 100 of these buzz bombs were fired into England. There were 94 B-24’s on this attack on V-1 facilities.

On May 24th, the date of the second mission, 400 B-24s bombed airfields in France.

Above: Patch of Uncle John’s Squad 733, 453 Bomber Group.

The 3rd mission was May 27, 1944, when they bombed rail yards near Saarbrucken, Germany. Although they did not run into any fighter planes, the squad was hit by intense flack and the engineer was wounded. John noted that two planes were lost on the 4th mission, and the Engineer was still absent from his injuries. The official report from that date stated “Opposition is heavy and 24 HBs [heavy bombers] are lost on mission.”

D-Day, the day for the invasion of Europe, was set for June 4. Bad weather forced D-day to be pushed back. Instead of supporting the Normandy invasion, 400 heavy bombers of the 8th Air Force, including John’s, hit airfields, railway junctions and bridges. These targets hurt the ability of the Nazi’s to provide reinforcements into the Normandy peninsula. No bombers were lost this day.

John’s 7th mission was over Caen, France on June 6, 1944. D-Day. The 8th Air Force had now reached its top strength. 1,729 heavy bombers of the 8th Air Force dropped 3,596 tons of bombs. Only 3 bombers were lost. That day John wrote in his logbook:

Mission #7 (71) June 6, 1944. Caen, France. “D”-Day. No fighters. No flak Time 0500 Results - unobserved (GH) Engineer still absent. 2300 Gal Gas. Trouble with bombay doors.

The eighth mission’s target was a railroad bridge at Rennes, France. The bridge was on the Brest Peninsula, just west of the port of LeHavre, the port from which many Swiss immigrants had departed. Again the purpose was to knock out the ability of the Nazi’s to provide support for the defenders of Normandy.

The next two missions, #9 and #10, were two more railroad bridges on the Brest Peninsula over the Loire River, east of Soumur, France. These bridge attacks prevented the Nazis from resupplying their forces in Normandy.

The 13th mission, June 19, 1944, was another attack on the V-Bomb sites, which were now active and terrorizing London as retribution for the invasion. The Engineer was still missing, as was the nose gunner, but no enemy fighters defended the target. 52 - 100 pound bombs were dropped on the Fienvillers, France site, in spite of intense flak that damaged the hydraulic system.

Now the Allied Command began to target deep into Germany. Mission #16 on June 28th hit the railroad yards at Saarbrucken, Germany, where the bombers took intense flak. The next day’s mission, Mission #17, was an aircraft factory and airfield near Dessan, Germany. John noted “Intense flak. Results - Good. Good Fighter support.”

The 18th mission was flown on July 2, 1944, and was a renewed attack on the V-bomb supply depots, this time at St. Omer, France. Later that day John received a temporary promotion from 1st Lt. to Captain.

They flew their 19th mission on July 6th, 1944. The assignment: directly attack a pilotless plane (V-weapon) installation at Belloy Sur Somme northwest of Amiens France. John notes “Moderate - but accurate flak. 6 x 12 hole in #1 engine - Large hole in left aileron trim tab.”

John’s log book for the 22nd mission on July 11, 1944 records:

Controls frozen on instrument take off in heavy overcast conditions. German broadcasting system claims destruction of town. Flak intense over target. Time - 09:15. 5 - 1000# G.P. - one hung up - had to be chopped loose over channel.

The official Air Force report for July 11, 1944 states that 969 heavy bombers from the 8th Air Force attacked Munich. Twenty bombers and 4 fighter planes failed to return to base. The one bomb John’s plane did not drop had hung up and was chopped loose over the English Channel so they could land safely.

Even though they had flown for almost ten hours the day before, Mission #23 was a return trip to Munich, this time to hit the railroad marshaling yards. This was a P.F.F. mission, which means there was Pathfinder Plane that had advanced navigation equipment that led the squadron. The Pathfinders dropped flares on the targets. John’s B-24 encountered intense flak over the target, but managed to drop their load of six 500# general purpose bombs and four incendiary bombs on the marked location. Total air time was 9.5 hours.

Mission #24 was the third mission in three days over Germany. This was another Pathfinder mission, this time an attack on the railroad marshaling yards at Saarbrucken, Germany, where they again took intense flak over the target. Finally the crew got two days off.

Mission #25 should have been their last. On July 16, 1944, they made another run at the Saarbrucken railroad marshaling yards, led again by the Pathfinders, with moderate flak over the target. Eleven heavy bombers and 3 fighter planes would be lost that day. But this was not to be their last mission, although they had flown the mandatory 25 missions. The war was at a tipping point. The Allies had not been able to break out of Normandy.

The July 18th mission would be a different type of run. Rather than a nine hour roundtrip deep into Germany, they were sent on a seven hour flight back to Normandy. The Germans were massing their troops to prevent the Allies’ breakout. John’s log book describes it best:

Mission #26 (#109) 18 July 1944 - Caen, France. Ground Troops & vehicles. Clear over Target area. 155 mm flak very accurate. We lead a shot up plane to a landing field 5 miles northeast of Selsey. Bill circled till he landed safely. Results - Complete area hit. 0700. Bombload - 312 - 16# frags.

July 19th and 20th (missions #27 and #28) would see back to back flights deep into Germany for bombing of airfields, a jet propulsion ME 263 fighter plane depot, and Messerschmidt factory and airfield, with destruction of the targets. Heavy flak was reported on nearly the entire route both days. 15 heavy bombers and 7 fighters were lost on July 19, and 19 heavy bombers and 8 fighters failed to return on July 20th.

It was about this time that John and his crew received some chilling instructions. Some pilots, overwhelmed by the continuously increasing number of missions before their tour of duty was over, were dumping their bomb loads and heading to Switzerland, where they would surrender. John’s crew was told to shoot down any U.S. planes that abandoned their mission.

As my cousin Daren used to tell it, “they put the farm boys in the driver’s seat because they knew they would do what needed to be done. No matter what.”

Mission #29, 24th of July, saw a return to Normandy in support of the US First Army offensive, Operation COBRA, which sought to penetrate the German defenses west of St. Lo and secure Coutances. The target was German troops and vehicles. 52 - 100 pound bombs were loaded. Flak was moderately accurate. But John did not drop any bombs: “for fear of hitting our own troops only 1500 yards away.” More than 25 Americans were killed and 130 were wounded by “friendly fire” bombs that day.

The next day, July 25th, was a return flight to Saint Lo, with the same target. John’s log book reports:

Log Book of Captain John C. Good, Mission #30 (#114). 25 July 1944.

The official Air Force Log states:

1,581 bombers and 500 fighters are dispatched to support a US First Army assault (Operation COBRA) with saturation bombing in the VII Corps area in the Marigny-Saint-Gilles region, just W of Saint-Lo; 5 bombers and 2 fighters are lost; 843 of 917 B-17s and 647 of 664 B-24s hit the Periers/St Lo area and 13 B-17s hit targets of opportunity; 1 B-17 and 4 B-24s are lost, 2 B-24s are damaged beyond repair and 41 B-17s and 132 B-24s are damaged; 9 airmen are WIA and 46 MIA. Escort is provided by 483 P-38s, P-47s and P-51s and also provide escort for Ninth Air Force B-26s; they claim 12-1-3 Luftwaffe aircraft in the air and 2-0-0 on the ground; 2 P-51s are lost (pilots are MIA) and 5 damaged. Due to a personnel error, bombs from 35 bombers fall within US lines; 102 US troops, including Lieutenant General Lesley J McNair, are killed and 380 wounded.

John and his crew finally got three days off, no doubt while their plane was repaired or replaced and they found a new belly gunner. Mission #31 involved oil storage depots near Paris, but heavy cloud cover completely obscured the target and no bombs were dropped. The Allies did break out of Normandy and continued their assault on Hitler’s Fortress Europe.

Mission #32 targeted the synthetic oil refineries at Bremen, Germany. They dropped their bombs in spite of intense flak at the target. John’s log book, now in larger print and shaky, reports that this was a Pathfinder, or “P.F.F. mission.” The official Air Force Mission description states:

Of 473 B-24s, 442 hit Bremen/Oslebshausen oil refinery, 2 hit targets of opportunity and 1 hit Cuxhaven; 2 B-24s are lost and 96 damaged; 3 airmen are KIA, 2 WIA and 15 MIA. Escort is provided by 106 of 109 P-51s.

Mission #33 was July 31, 1944. 447 B-24’s attacked deep into the heart of Germany, escorted beyond the Dutch coast by 3 fighter groups. John’s B-24 was assigned to bomb the I.G. Faben Chemical Works. They encountered heavy 155 mm flak and enemy fighters, but successfully dropped 52 - 100 pound bombs on the chemical works.

I.G. Farben used slave labor from concentration camps, and manufactured the poison gas, Zyklon B, that killed over one million people in gas chambers during the Holocaust. After the war, as part of the Nuremberg trials, 3 IG Farben directors were tried and convicted of war crimes against humanity.

The official Air Force Mission description states:

447 of 486 B-24s bomb the chemical works and city at Ludwigshafen, and SW part of the city of Mannheim; 6 B-24s are lost and 186 damaged; 1 airman is KIA, 7 WIA and 62 MIA. Escort is provided by 135 P-38s; 1 is damaged.

The bombing of IG Farben Chemical Works would prove to be John’s final mission. He and his crew flew their Michigan-built Ford B-24 Liberator on 33 missions, 16 in July 1944 alone. John flew a total of 210 hours and dropped 180,200 pounds of bombs, a strong contribution to the defeat of the Nazis. His last log book entry, in large block letters, states:

The crew flew a total of 33 missions from May 22nd to July 31st. Their luck held, for the most part. The belly gunner was seriously injured on Mission #30, and, as mentioned, the engineer, Thomas E. Bent, was injured by flack on the third mission. An adverse reaction to a tetanus shot caused Thomas Bent to miss ten flights. As a result he was still flying missions to complete his tour of duty when the rest of the crew went stateside. In a letter published in the 2nd Air Division Newsletter in the 1980’s Mr. Bent stated in part:

After my original crew completed their tour of duty and were shipped back to the states I flew with several crews as a spare when needed. On 19 October 1944 on my 32nd mission to the Frankfurt area [which would have been his last] we received direct flak hits. … All the crew bailed out. … I spent the rest of the war as a POW in Stalag Luft IV and made the infamous march across Germany in the winter of 1944-1945.

After the war was over, Thomas Bent was the supervisor assigned to prepare the B-24 “Strawberry Bitch” for flight from Tucson, Arizona to the Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson AFB, Dayton, Ohio. The “Strawberry Bitch” is one of the few surviving B-24 bombers still in existence, and is still on display at Wright-Pat.

Photo courtesy of Ernest C. Clark and the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

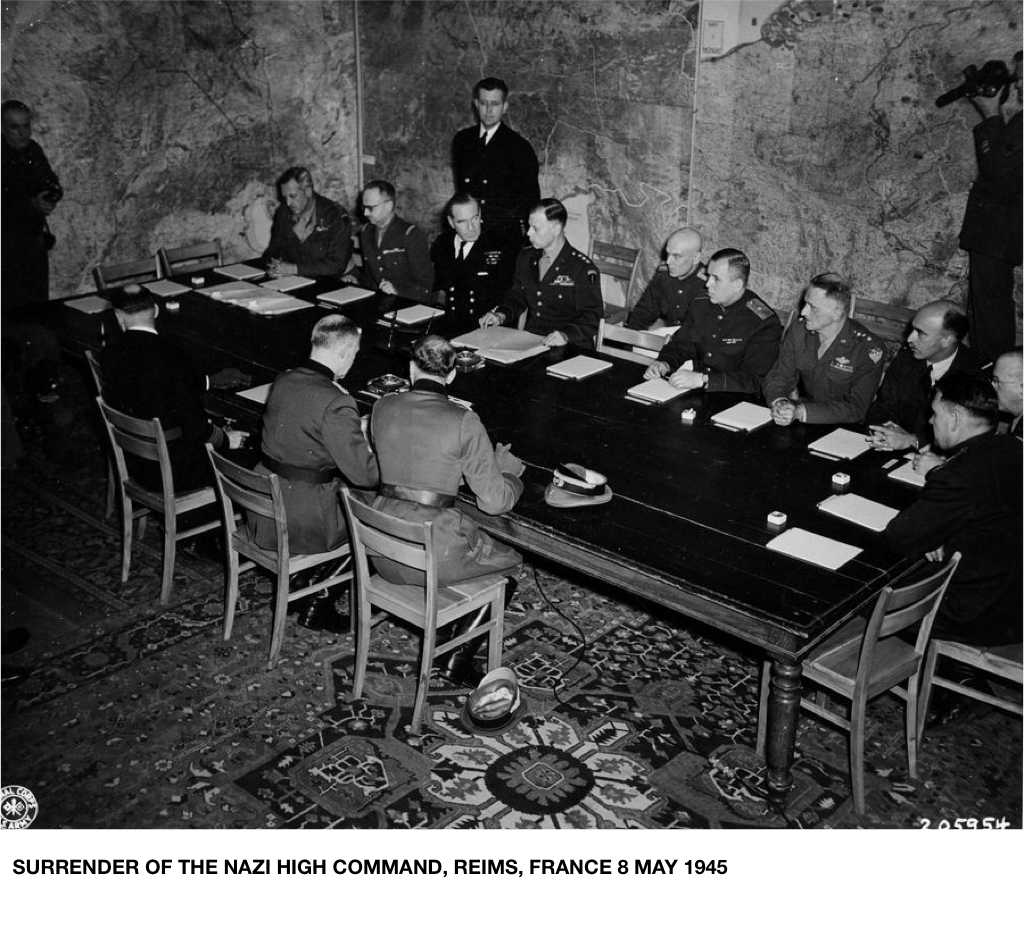

On May 8, 1945, the German High Command surrendered at Eisenhower’s Headquarters in Reims, France.

On September 2, 1945, the formal surrender documents of the Japanese were signed aboard the USS Missouri, designating the day as the official Victory over Japan Day (V-J Day). These two racist regimes had sought world dominion. Only the United States entry into the war prevented these regimes from dominating the world.

Good read! My Dad's time nearly parallels your uncle's. Dad was from Toledo Ohio, and Mom from Sandusky also. Mom's Dad was a dentist in downtown Sandusky. Dad was a pilot in 453rd, also 733rd squadron, with 30 missions 4/27/44 to 8/5/44.

I would love kind of a picture / poster framed with these patches and summary (nazis killed, maybe a map with locations hit??) I would definitely hang it in our house - maybe I can try in my free time or if you have any thoughts lmk!!!)